Although she regularly said her middle initial stood for “Pay it no mind”, Marsha P. Johnson proved to be a difficult person not to notice. Though Johnson is commonly referred to using female pronouns (she/her/hers) — and I’ll be doing that here — her actual gender identity is a bit of a mystery. She variously described herself as gay, a transvestite, and as a (drag) queen — though words like “transgender” really weren’t being widely used yet during her lifetime. My personal opinion is that she would probably identify as gender non-conforming or non-binary, but make your own judgments.

Although she regularly said her middle initial stood for “Pay it no mind”, Marsha P. Johnson proved to be a difficult person not to notice. Though Johnson is commonly referred to using female pronouns (she/her/hers) — and I’ll be doing that here — her actual gender identity is a bit of a mystery. She variously described herself as gay, a transvestite, and as a (drag) queen — though words like “transgender” really weren’t being widely used yet during her lifetime. My personal opinion is that she would probably identify as gender non-conforming or non-binary, but make your own judgments.

Johnson was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey on August 24, 1945 — one of seven children — and was named Malcolm Michaels Jr by her parents, Malcolm Michaels Sr and Alberta Claiborne. They were not, from all accounts, a particularly open-minded family and Claiborne was said to believe that being a homosexual was like being “lower than dog.” Johnson was raised in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and remained a devout, practicing Christian for her entire life.

At the age of five, Johnson began to wear dresses — but stopped because she was harassed and teased by neighborhood boys. Some time during this period, Johnson was sexually assaulted by a boy who was roughly the age of 13. In 1963, Johnson graduated from Edison High School and promptly moved to New York City with $15 and a bag of clothing. By 1966, she was waiting tables, engaging in sex work, and living on the streets of the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan.

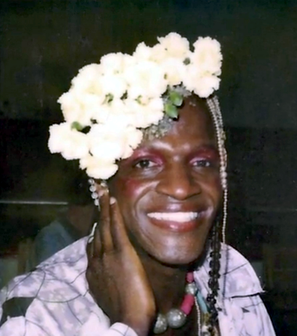

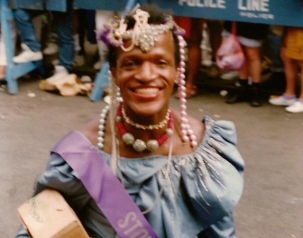

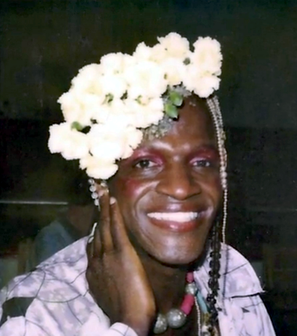

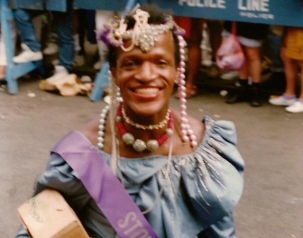

She also began to perform as a drag queen — initially going by the name “Black Marsha” before settling on Marsha P. Johnson. She was often recognizable for having flowers in her hair — something she began doing after sleeping under flower sorting tables in Manhattan’s Flower District. She usually had on bright colored wigs, shiny dresses, and long flowing robes. Marsha was known to be peaceful and fun, but there was a violent and short-tempered side to her personality (which her friends commonly called “Malcolm”) — leading some to suspect that she suffered from schizophrenia. Between her sex work and her occasional violent outbursts, Johnson claimed to have been arrested more than a hundred times.

She also began to perform as a drag queen — initially going by the name “Black Marsha” before settling on Marsha P. Johnson. She was often recognizable for having flowers in her hair — something she began doing after sleeping under flower sorting tables in Manhattan’s Flower District. She usually had on bright colored wigs, shiny dresses, and long flowing robes. Marsha was known to be peaceful and fun, but there was a violent and short-tempered side to her personality (which her friends commonly called “Malcolm”) — leading some to suspect that she suffered from schizophrenia. Between her sex work and her occasional violent outbursts, Johnson claimed to have been arrested more than a hundred times.

When the Stonewall Inn began to permit women and drag queens inside, Johnson was one of the first to begin regularly visiting the bar. Some witnesses have even credited her with starting off the riots in 1969. Although this claim has certainly gained traction and become the popular version of events, she likely was not the woman who sparked off the Stonewall Riots by throwing the legendary “first brick” — this was also rumored, and was perhaps more likely to be Jackie Hormona or Zazu Nova by eyewitnesses — Johnson did have one particularly iconic, though unconfirmed, moment in the riots. She is said to have shouted “I got my civil rights!” and thrown a shot glass at a mirror. ( Some said this — the “shot glass heard round the world” — was the moment that started the riots, but Johnson herself disputed this. According to Johnson, word of the riots reached her and she immediately went to collect her friend Sylvia Rivera so they could join in — but Rivera was sleeping on a bench. According to Johnson, she arrived at about 2:00 am, forty minutes after the riots began. (I guess word traveled fast!) There are many reports that on the second night of rioting, Johnson climbed up a street lamp with a purse that was loaded down with a brick — which she dropped through the windshield of a police car. Though there’s a lot of stories about those riots, and a lot of confusion about the details it is very clear that Johnson was there and made a noticeable impact.

Although she’d been an activist before, Johnson became a real leader in the LGBT movements that followed the riots. In 1970, she and Sylvia Rivera founded the Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries (STAR) — an organization that provided community support for transgender youth. She also joined the Gay Liberation Front and participated in the Christopher Street Liberation Pride rally that commemorated the first anniversary of Stonewall (and was, essentially, the creation of the Pride festivals we celebrate.) At one rally in the early 70’s, Johnson was asked by a member of the press what they were protesting for –Johnson shouted into the reporter’s microphone “Darling, I want my gay rights now!”

Johnson once said, “I was no one, nobody, from Nowheresville until I became a drag queen. That’s what made me in New York, that’s what made me in New Jersey, that’s what made me in the world.” In 1972, she began to perform periodically with the international drag troupe Hot Peaches. She was also continuing to work as a sex worker, taking the money she (and Rivera) earned from that business to help pay the rent for the housing for transgender youth that STAR had established that year. Johnson also took on an active role mentoring all of the youth in their care, becoming a “drag mother” even to those who were not performers. Although STAR declined and closed in 1973, it was a groundbreaking organization and the shelter that it provided queer youth was truly revolutionary.

In 1973, Johnson also performed with the Angels of Light drag troupe — taking on the role of “The Gypsy Queen” in their production of “The Enchanted Miracle”. That same year both Johnson and Rivera were banned from participating in New York’s gay pride parade — the committee organizing the parade felt that drag queens and transvestites brought negative attention and gave the cause “a bad name.” In response, Rivera and Johnson marched ahead of the beginning of the parade.

In 1973, Johnson also performed with the Angels of Light drag troupe — taking on the role of “The Gypsy Queen” in their production of “The Enchanted Miracle”. That same year both Johnson and Rivera were banned from participating in New York’s gay pride parade — the committee organizing the parade felt that drag queens and transvestites brought negative attention and gave the cause “a bad name.” In response, Rivera and Johnson marched ahead of the beginning of the parade.

In 1975, Andy Warhol took pictures of Johnson for his “Ladies and Gentlemen” series. Johnson’s success as an activist and a performer, as well as her regular appearances throughout the decade, earned her the nickname “Mayor of Christopher Street.”

In 1975, Andy Warhol took pictures of Johnson for his “Ladies and Gentlemen” series. Johnson’s success as an activist and a performer, as well as her regular appearances throughout the decade, earned her the nickname “Mayor of Christopher Street.”

By 1979, Johnson’s mental health was beginning to decline quite severely. Her aggressive side was coming out more often, and a Village Voice article called “The Drag of Politics” listed all of the Manhattan gay bars from which Johnson had been banned. In 1980, a friend named Randy Wicker invited Johnson to stay with him for a particularly cold night and the two remained roommates for the rest of Johnson’s life. This was — as far as I can tell — the first time Johnson had a permanent address since moving to New York in 1963.

In the 1980’s, Johnson began to work with ACT UP as an organizer and marshal, and was a prolific AIDS activist. She made this her primary focus for the last few years of her life. On July 6, 1992 — just after that years New York Pride festivities — she was found dead in the Hudson River with a large wound in the back of her head. The police ruled her death a suicide — despite pressure from the community and the fact that she had a wound in the back of her head. One witness had spoken of Johnson’s fragile mental health to the police — which was all the police, who had no interest in investigating a black queer person’s death, needed despite witness testimonies also describing Johnson being harassed by a gang. Another witness claimed to have heard a man brag about killing a drag queen named Marsha. The police did allow Seventh Avenue to be closed so that Johnson’s friends could spread her ashes out over the river.

In 2012, an activist named Mariah Lopez was finally successful in convincing the police to re-open Johnson’s case and investigate it as a homicide. That was also the year that the first documentary about Johnson was released: Pay It No Mind — The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson. This documentary included footage from an interview that had been filmed only ten days before Johnson’s death. Fictionalized versions of Johnson also appeared in the films Stonewall (released in 2015) and Happy Birthday Marsha! (released in 2016.) In 2017, another documentary was released — The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson — which followed the Anti-Violence Project’s Victoria Cruz investigating Johnson’s death on her own. Despite all of these tributes, it wasn’t until 2018 that the New York Times published an obituary for her.

Johnson — with her friend Sylvia Rivera — will be honored with a monument in Greenwich Village, near Stonewall. This is perhaps most fitting for Johnson, since she was quite insistent about moving the Stonewall monument from Ohio to Christopher Street in New York City in 1992 — famously saying “How many people have died for these two little statues to be put in the park to recognize gay people? How many years does it take for people to see that we’re all brothers and sisters and human beings in the human race? I mean how many years does it take for people to see that we’re all in this rat race together?”

Johnson may not have “thrown the first brick” at Stonewall, but she led the fight for LGBTQ+ equality in every other way. Randy Wicker said of Johnson that she “rose above being a man or a woman, rose above being black or white, rose above being straight or gay”, while Rupaul described her as “the true Drag Mother.”

So, while we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, let’s all pay plenty of mind to Marsha P. Johnson — and to the other heroes who stood up that day and said “Darling, I want my gay rights now!”

I wish this article was going to be longer, but I have honestly scoured the internet for more information on this person, and I have almost nothing. Nevertheless, Jackie Hormona contributed the

I wish this article was going to be longer, but I have honestly scoured the internet for more information on this person, and I have almost nothing. Nevertheless, Jackie Hormona contributed the

Although she regularly said her middle initial stood for “Pay it no mind”, Marsha P. Johnson proved to be a difficult person not to notice. Though Johnson is commonly referred to using female pronouns (she/her/hers) — and I’ll be doing that here — her actual gender identity is a bit of a mystery. She variously described herself as gay, a transvestite, and as a (drag) queen — though words like “transgender” really weren’t being widely used yet during her lifetime. My personal opinion is that she would probably identify as gender non-conforming or non-binary, but make your own judgments.

Although she regularly said her middle initial stood for “Pay it no mind”, Marsha P. Johnson proved to be a difficult person not to notice. Though Johnson is commonly referred to using female pronouns (she/her/hers) — and I’ll be doing that here — her actual gender identity is a bit of a mystery. She variously described herself as gay, a transvestite, and as a (drag) queen — though words like “transgender” really weren’t being widely used yet during her lifetime. My personal opinion is that she would probably identify as gender non-conforming or non-binary, but make your own judgments. She also began to perform as a drag queen — initially going by the name “Black Marsha” before settling on Marsha P. Johnson. She was often recognizable for having flowers in her hair — something she began doing after sleeping under flower sorting tables in Manhattan’s Flower District. She usually had on bright colored wigs, shiny dresses, and long flowing robes. Marsha was known to be peaceful and fun, but there was a violent and short-tempered side to her personality (which her friends commonly called “Malcolm”) — leading some to suspect that she suffered from schizophrenia. Between her sex work and her occasional violent outbursts, Johnson claimed to have been arrested more than a hundred times.

She also began to perform as a drag queen — initially going by the name “Black Marsha” before settling on Marsha P. Johnson. She was often recognizable for having flowers in her hair — something she began doing after sleeping under flower sorting tables in Manhattan’s Flower District. She usually had on bright colored wigs, shiny dresses, and long flowing robes. Marsha was known to be peaceful and fun, but there was a violent and short-tempered side to her personality (which her friends commonly called “Malcolm”) — leading some to suspect that she suffered from schizophrenia. Between her sex work and her occasional violent outbursts, Johnson claimed to have been arrested more than a hundred times. In 1973, Johnson also performed with the Angels of Light drag troupe — taking on the role of “The Gypsy Queen” in their production of “The Enchanted Miracle”. That same year both Johnson and Rivera were banned from participating in New York’s gay pride parade — the committee organizing the parade felt that drag queens and transvestites brought negative attention and gave the cause “a bad name.” In response, Rivera and Johnson marched ahead of the beginning of the parade.

In 1973, Johnson also performed with the Angels of Light drag troupe — taking on the role of “The Gypsy Queen” in their production of “The Enchanted Miracle”. That same year both Johnson and Rivera were banned from participating in New York’s gay pride parade — the committee organizing the parade felt that drag queens and transvestites brought negative attention and gave the cause “a bad name.” In response, Rivera and Johnson marched ahead of the beginning of the parade. In 1975, Andy Warhol took pictures of Johnson for his “Ladies and Gentlemen” series. Johnson’s success as an activist and a performer, as well as her regular appearances throughout the decade, earned her the nickname “Mayor of Christopher Street.”

In 1975, Andy Warhol took pictures of Johnson for his “Ladies and Gentlemen” series. Johnson’s success as an activist and a performer, as well as her regular appearances throughout the decade, earned her the nickname “Mayor of Christopher Street.”